On Reading And/Or Thinking

The Experience of the World Elsewhere

Been a while, hasn’t it? I’m deep into writing the book under contract to U Chicago Press, so I haven’t been tending this garden. Other Substack proprietors often take a breather by telling you what they’re reading and watching. I haven’t been able to do that much lately because the stuff I’m reading is mostly “French Theory” of the esoteric kind, which appeals only to specialists and academics and nerds like me.

Jean Wahl is the preoccupation for now. He’s probably the most important French intellectual of the 20th century, and the most unappreciated, except in some recent books that take exception to the story told by Vincent Descombes, Michael Roth, and Judith Butler, which makes Alexandre Kojeve’s reading of Hegel’s Phenomenology the detonating event in the making of post-structuralism, ca. 1930s-1970s. I treat Wahl as such, anyway, and try to demonstrate that his importance as an interpreter of Hegel, Kierkegaard, and Heidegger on the French scene—his profound effect on subsequent thinkers, such as Sartre, Hippolyte, Levinas, Deleuze, and Derrida, not to mention Kojeve himself—is a result of his prior immersion in Anglo-American empiricism, specifically the pragmatism and pluralism of William James and Josiah Royce.

__________

Anyway, I’m also writing a paper on John Diggins for a conference next week at the CUNY Grad Center, in which I’m focused, more or less, on his Lost Soul of American Politics (1986). I hope this paper will atone for my performance at the same place in November 2009, when, as a participant on a panel that was supposed to be celebrating his life and work—he had recently passed—I explained why his least academic book, The Promise of Pragmatism (1994), was laughable because it had nothing to do with the ostensible subject of the title, having somehow become a loving tribute to Henry Adams.

With members of his mourning family staring at me from the front row, I speculated that perhaps this lark of a book—it’s almost autobiographical in its relentless identification with the hapless Henry, who couldn’t accept the world as it actually existed—happened because Jack was in love, not with old Henry himself but with some muse that had led him away from his contractual obligation to tell us how and why pragmatism never lived up to its promise of intellectual liberation from the shackles of the Platonic tradition. It did not go over well. The hushed silence that greeted the paper was amplified, as it were, by the comment of a colleague as I left the auditorium: “Nice going, Jim, did yourself proud with that one.” I didn’t hear the sarcasm until later, at the cocktail party, where it was emphasized by the stricken looks on the faces of everyone I encountered, including two of those grieving family members. Their uniform expression said: “Good Christ, how could you?”

__________

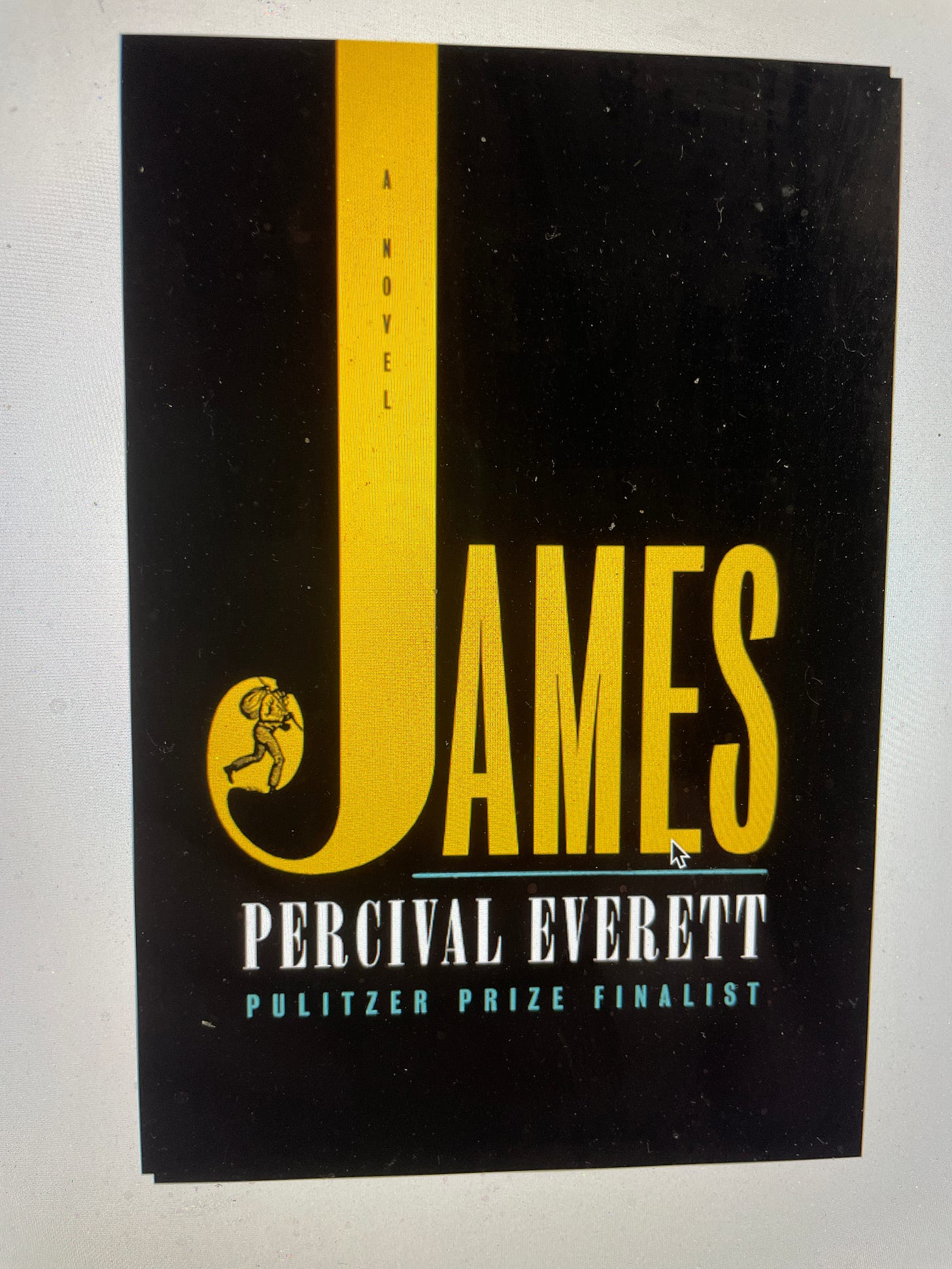

Just now, however, I’m reading James: A Novel, by Percival Everett, a re-telling of Huck’s adventures from Jim’s point of view, because I watched a movie based on Erasure, his last book, called “American Fiction,” with the brilliant Jeffrey Wright as the lead—and because the brilliant Matt Seybold wrote a stunning review of the new novel, which shows how this fiction incorporates and comments on the literary criticism that has always determined the reception of that 19th-century ur-text, The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. The link to Matt’s review is below, at bottom.

I’m only a third of the way through this meditation on language, which constantly switches codes between “Black” and “White” English, thus situating the characters in the respective prison houses of their languages and their strict corollaries in the objects that can be designated or addressed, and the subjects that are assumed or created accordingly. It’s dizzying, and yet calmly, weirdly explanatory, making what is evident yet unknown—how language determines us even as we express ourselves not “with” but in and through it—seem obvious without argument.

For now, I just want to highlight a passage from the end of Chapter 11, where Jim, not yet James, tells us of the exhilaration he felt when he realized what it means to read a book by yourself, for your self. He taught himself (and his fellow slaves) to read a while back, and now he’s waiting on the raft for Huck to fall asleep so he can read the books they’ve recovered from an abandoned riverboat:

“I really wanted to read. Though Huck was asleep, I could not chance his waking and discovering me with my face in an open book. Then I thought, How could he know that I was actually reading? I could simply claim to be staring dumbly at the letters and words, wondering what in the world they meant. How could he know? At that moment the power of reading made itself clear and real to me. If I could see the words, then no one could control them or what I got from them. They couldn’t even know if I was merely seeing them or reading them, sounding them out or comprehending them. It was a completely private affair and completely free and, therefore, completely subversive.

“ . . . The small thick book I’d wrapped my fingers around was the novel. I had never read a novel, though I understood the concept of fiction. It wasn’t so unlike religion, or history, for that matter. I pulled the book from the bag. I checked to see if Huck was till sleeping soundly and then I opened it. The smell of the pages was glorious.

“In the country of Westphalia . . .

“I was somewhere else. I was not on one side of that damn river or the other. I was not on the Mississippi. I was not in Missouri.”

Think of all that is encapsulated here. The revolution of the Word. What the printing press did. Why the Protestants’ insistence on reading the Bible in translation, in the vernacular languages of the people, was a revolutionary act. How the transition from an oral to a print culture, which wasn’t accomplished until the 19th century—almost 2000 years after the Word of God was written down, and that epochal event occurred only five centuries after a written, alphabetical language was invented in Attica—changed the way we think, literally, by removing the reciprocity of speaker and listener in the formation of ideas, and in the oral transmission of law, commandments, strictures, habits, customs, methods. And thus put hierarchies in question.

Also, how that transition changed what we could think by urging both readers and writers to go beyond what was already known, something that was dangerous, and therefore frightening, in a world that preserved memory in speech, in poetic forms that were easily replicated for oral transmission from one generation to the next. Why that transition made the prospect of timeless truth, the kind that can be logically demonstrated but probably not acted out in real time—as it had to be in an oral culture—seem within reach, because now, once written down, it could last forever.

The individuality required of reading, the way you must seal your self off from the “outside world” in order to concentrate on the printed page. And yet the infinite scope of the world now available to you as you read, in private, all by yourself, “alone with your thoughts” because a perfect stranger—an author who perhaps writes to you and for you from another century—has let you in on his, or hers.

The linearity of the lines, the way the words separate and the paragraphs get divided are late additions to printed texts—original editions of the paradigmatic modern novel, Don Quixote, for example, have no space between words and no paragraph breaks, making it totally illegible to a modern reader—but these visual cues hurry you along at a brisk pace in a very straight line, left to right, on toward an ending you anticipate and imagine; and so they standardize story-telling, getting you used to beginnings, middles, ends, and, with them, the characters, individuals like you, and the unique moral agency they bring to their worlds.

That is what it means to read a book by yourself, for your self. It is to know yourself by getting outside your self. It’s completely subversive because you’re not in Missouri, nor Kansas, either, Dorothy, nor anyplace else you’ve ever been.

And now, is that feeling becoming unavailable, because reading itself is changing along with the material—the “content’’—of what we read, as everything is subjected to the digital regime? I have no idea. But so far, I still think we’re living through another revolution of the Word, not a counter-revolution that is robbing us of our literacy. And you?

__________

https://www.clereviewofbooks.com/writing/percival-everett-james?fbclid=IwAR0ud2AIuWqW7ilju66tBriPWBzkGk8NwK3B2LseSG7yAnC5KhVAly0Ff2I_aem_AWW4x_u_3bT63OMdKF4X8FX-Qt8oBbKYAnU-LWasbnHUCfRyVeZHna1smNAw0N8BUa37uM--BtTr2CvhISEtNXkv

Hey Tim, Me neither, with the novels, unless I'm in a car on a long trip, and the girlfriend puts on an audio book. But when Dwight Garner raves and Matt Seybold (the regnant authority on Twain) seconds the motion, you gotta pay attention. How you doing?

Courtesy of your reflection, I've added Everett's novel to my list. And I don't often read novels!