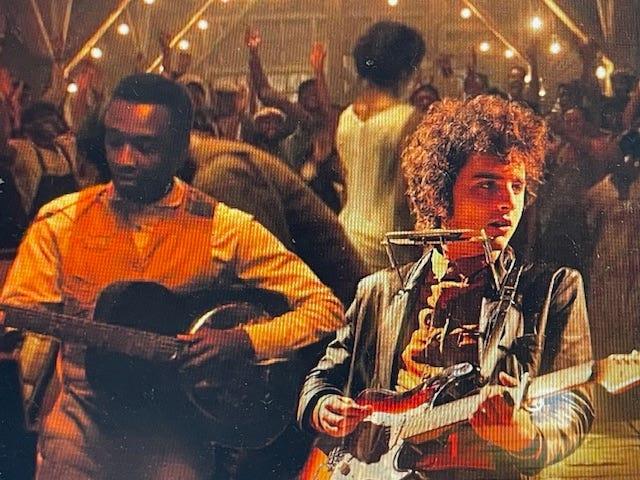

Sinners in the Hands of a Complete Unknown

A Review of Political Stories Told With Music, and Vice Versa

https://libertiesjournal.com/online-articles/sinners-in-the-hands-of-a-complete-unknown/

__________

That’s the link to my review of “A Complete Unknown” and “Sinners,” just published by Liberties. Thanks to Celeste Marcus, the managing editor there. No paywall!

The opening paragraphs go like this:

Can the blues set you free? It’s hard to say, because, as you have probably heard from a reliable source whose play lists favor classic rock, “writing about music is like singing about architecture.” Meaning that it’s kind of pointless, because there are no words for what music makes you feel — you can explain the immediate physical sensations induced by these sounds in terms of waves and frequencies, but it’s near impossible to provide a verbal transcript of the desires and the memories those sensations become when inscribed on your body.

Turns out that the line is a venerable commonplace first recorded in 1918, and that the original enlists a different set of skills: “it’s like dancing about architecture.” But this old twist makes the admonition all the more prohibitive, because dance music is of course the lowest common denominator in the affective universe we ascribe to music as such (see: American Bandstand, disco, Soul Train). The audiences in opera houses and concert halls know better than to get up and dance.

Their stillness is remarkable. To be sure, music is the most cerebral, most immaterial of media; but it engages the body more easily and effectively than any other medium, mainly because the order and pitch of certain notes (as structured by rhythm) will evoke desire or anxiety, thus expectations of satisfaction, release, or resolution, in listeners. At least they will in the post-Renaissance western world, where tonal-harmonic music became the cultural norm, and where such expectations could, therefore, be sonically produced as the occasion required — typically by treating dissonance as both deviation from and promise of equilibrium, of musical resolution.

So the mind/body problem that has shaped western philosophy from its founding moments is near at hand in the interpretation of music, regardless of how, or whether, listeners are equipped to express and explain their responses. And with that philosophical problem, that dissonance, comes the tentative resolution we call our selves; for these phenomena derive immediately, necessarily, from our everyday enactment of the relation between mind and body, for example in how we respond to inchoate desires, by repressing, deferring, or gratifying them. In reminding us quite forcefully of our bodies, music tends to unsettle this relation, and therefore to disrupt the continuity of our selves. So it makes us reach for memories — the mostly futile search we conduct in words and images — as the means of restoring and maintaining that continuity.

These proximities are what the brilliant musicologist Susan McClary had in mind when she declared that “music is always a political activity, and to inhibit criticism of its effects for any reason is likewise a political act.” . . . .

Jim, I've read a good deal of your work-- and have thought, more than once .. hmm where is dylan in or for Jim? no clue in this intro, but no pay wall to the real thing. I'll get back to you...btw I'm the scribbler looking at Said, Foner, Montgomery. I've decided they qualify as Wilbury's. bob